- Home

- Melanie P. Merriman

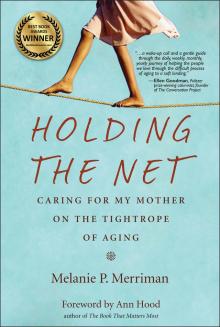

Holding the Net

Holding the Net Read online

HOLDING THE NET

HOLDING THE NET

Caring for My Mother on the Tightrope of Aging

MELANIE P. MERRIMAN

WITH A FOREWORD BY

Ann Hood

© 2017 by Melanie P. Merriman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States

10987654321

GREEN WRITERS PRESS is a Vermont-based publisher whose mission is to spread a message of hope and renewal through the words and images we publish. Throughout we will adhere to our commitment to preserving and protecting the natural resources of the earth. To that end, a percentage of our proceeds will be donated to environmental activist groups and a charity of the author’s choice. Green Writers Press gratefully acknowledges support from individual donors, friends, and readers to help support the environment and our publishing initiative. Green Place Books curates books that tell literary and compelling stories with a focus on writing about place—these books are more personal stories/memoir and biographies.

Giving Voice to Writers & Artists Who Will Make the World a Better Place

Green Writers Press | Brattleboro, Vermont

www.greenwriterspress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

E-BOOK ISBN: 9780999076613

COVER PHOTO: JÜ[email protected]

Lucky Girl: Words and music by Joni Mitchell.

Copyright © 1985 Crazy Crow Music. All rights excluding print administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing. Exclusive print rights administered by Alfred Music.

All rights reserved. Used by permission of Alfred Music.

THIS BOOK WAS PRINTED ON 30% PCR STOCK.

PRINTED BY THOMSON-SHORE.

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Chapters 1-25

Body Flow, poem

Suggested Resources

Suggested Additional Reading

Acknowledgments

Book Club Discussion Guide

Foreword

IN THE LAST ACT OF Macbeth, the main character makes reference to “…that which should accompany old age, as honour, love, obedience, troops of friends.” Were truer words ever spoken? Honor, love, obedience, and troops of friends should accompany us into our old age—but how to accomplish that?

This was the goal Melanie Merriman and her sister Barbara had for their mother after their father died suddenly. At seventy-eight, Merriman’s mother was still able to live independently in the condo that she and her husband had shared. Active in her community, she played bridge, participated in not one but two book clubs, and edited The Comet, her condo association’s monthly newsletter. At that point, Merriman’s hope of making “the rest of her [mother’s] life the best it could possibly be” did not seem difficult.

Time marched on, however, and aging began to take its toll. One-third of people in the United States who are over sixty-five need some help in managing their daily lives; by the time they reach eighty-five (the fastest-growing segment of our population today), that number jumps to well over one-half.

Ten years after her husband died, Merriman’s mother—then eighty-eight—began to voice her desire to never be dependent on her daughters. “I’m going to stay in my condo until I die,” she told them two months before her eighty-ninth birthday. Yet friends were warning Merriman and her sister that their mother was slowing down, an idea they rejected at first. It’s difficult to accept that a parent is no longer “aging well.” My guess is that everyone reading this has faced a similar point in life, or watched a friend or family member deal with a parent (or both parents) as they struggle with independence, health issues, and emotional or mental decline.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, America’s population of persons aged ninety and older has tripled since 1980, reaching 1.9 million in 2010. Over the next forty years, that number will increase to 7.6 million. Wan He, the Census Bureau demographer, stated, “Traditionally, the cutoff age for what is considered the ‘oldest old’ has been 85, but people are living longer and the older population itself is getting older.” And getting older means needing more care. More than 20% of people in their nineties live in nursing homes, and over 80% of people in their nineties have at least one disability.

Grace Paley wrote: “Old age is another country, a place of strangeness, sometimes, and dislocation.” Melanie Merriman and her sister found themselves navigating that place of strangeness, which in today’s world includes supportive living arrangements, the health-care system, myriad professionals, and the person who is aging. In his poem “Affirmation,” eighty-nine-year-old poet Donald Hall wrote, “To grow old is to lose everything.” But Merriman—like adult children everywhere—vowed to make it otherwise for her mother. With honesty, nostalgia, humor, tenderness, and wisdom, she tells the story of their journey in Holding the Net: Caring for My Mother on the Tightrope of Aging.

Sixteen years after the phone call bringing the news that her father had died, Merriman’s mother died at the age of ninety-four. This is the story of those years. It is the story of mothers and daughters. It is the story of aging in America today. It is the story of failures and successes in the decisions required to help someone age well. Most importantly, it is not the story of just one mother and her daughters. It is all of our stories—ones already lived, or ones midstream, or ones about to happen. Read Melanie Merriman’s words for validation, for forgiveness, for guidance, for hope. The tightrope of aging contains all of these, and more. This book will hold your hand on that tightrope.

Ann Hood

May, 2017

Preface

WHEN MY EIGHTY-YEAR-OLD FATHER died suddenly, my mother dealt with her grief by keeping busy. She joined a second book club, played more bridge, and intensified her community activities. Though it was hard to imagine her slowing down, I knew things would change as she aged. With my father gone, I appointed myself to look after Mom. I wanted to make the rest of her life the best it could possibly be.

I reasonably expected that this wouldn’t be too difficult. First, my mother had the resources to pay for whatever care she might need. Second, I worked in the field of hospice and palliative care, so I knew more than most people do about illness, aging, and our overly complex medical system. Third, I had a supportive sibling: my sister, Barbara.

It turned out that my rational expectations could not have been more wrong. Despite my many distinct advantages, caring for my mother as she declined both physically and mentally proved humbling. Emotions overwhelmed reason, and my professional knowledge paled next to my lack of real-world experience. My sister Barbara and I desperately wanted to do the right things for our mother, but we were never sure what the right things were. Every decision pitted Mom’s desire for independence against our fear for her safety on what I came to think of as the tightrope of aging.

After Mom died, I looked up from my head-down focus on her immediate needs and realized that most of my friends—and even strangers I talked to in line at the grocery store or coffee shop—were living through some version of this tightrope walk with aging parents. I also found that in sharing our stories, we were giving each other something we desperately needed: validation that caring for a parent is unwelcome and unfamiliar for all concerned.

I wrote Holding the Net to help as many people in this situation as possible. People with aging parents who want to know what to expect. People who cared for an elderly parent who died, and wonder whether they did it well. Even aging parents themselves, who want, a

s my mother so desperately wanted, not to be a burden to their children.

I cannot offer a foolproof recipe for helping a parent age with grace. In my experience, the ingredients are too human, and the healthcare system is too flawed. But when children willingly offer support—and when, even more rarely, parents willingly accept that support—there can be moments that feel perfect. That is where grace comes in.

To help you find more of those perfect moments, and better deal with the difficult ones, I have laid bare both my successes and my failures in caring for my mother. I have shared what I knew going in—or discovered along the way—about supportive living arrangements, healthcare services, medical decision-making, professionals you can turn to for help, and more. While I don’t have all the answers, you can learn from my experience, and may feel comforted to see that uncertainty and confusion are normal when caring for an aging parent.

Everything in this book is true, and told as I remember it. While some of the dialogue is improvised, all of it is based upon actual conversations or written communication. The people and places exist, and for most of them, I have used real names. In cases for which I wanted to protect an identity, names have been changed.

There are three people without whom this book would never have come to be: Andrea Askowitz, who provided encouragement on the first day of my first writing class, and made me believe I could be a writer; my sister, Barbara, who helped with research, provided insightful feedback on multiple versions of the text, and often guided me to the truth; and my husband, Klein, whose love and support are the warp and weft of my personal safety net.

HOLDING THE NET

Chapter 1

THREE WEEKS BEFORE HIS EIGHTY-FIRST BIRTHDAY, my father died only moments after complimenting my mother on dinner—lamb chops, mashed potatoes, and asparagus. When my phone rang on that night of February 28, 1994, I was in Miami, some three hundred miles away, entertaining friends in the house I shared with my fiancé, Klein.

“Daddy’s gone,” Mom said as soon as I picked up the phone. I held the receiver in one hand and grabbed the kitchen doorknob with the other as I slid down the wall to the floor.

“What happened?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I was going to the kitchen to fix coffee after we ate, and I heard him cough and choke a little. Then he just stopped. I didn’t hear anything but the TV.”

“Was it a heart attack?” I asked.

“A stroke, I think. I went back to check on him, and his head was down. I grabbed his shoulders, and he was just limp. So I called 911. It happened so fast!”

“Mom, are you okay?” I was thinking about how and when I could get across the state to New Port Richey to be with her.

“I’m here with the rescue squad. They’ll stay with me until the funeral home comes. And Ginny is coming down. I think she’ll stay overnight if I want her to.”

Ginny, their second-floor neighbor, was a widow with a big extended Italian family that included good friends like my parents. I knew she would take good care of Mom.

“Oh, Mom, I’m never going to see him again, am I?” I was crying.

“No, honey.”

I knew exactly where the paramedics had found him—slumped in his chair in the sunroom of the condo. Every evening, my parents sat in the matching rattan chairs, on cushions decorated with brushstrokes of pale blue, violet, and pink. They watched the news, and maybe a documentary on PBS, while enjoying a dry martini and dinner served on teak TV tables. In the mornings, they drank coffee poured from a thermal carafe at the rattan table by the glass sliding doors, ate fruit and toast, and worked on the daily crossword puzzle while watching the occasional boat glide down the canal, just a few steps away.

“Kiss him for me. Please, Mom, kiss him on his cheek.”

“Okay, honey, I will.” My mother sounded overly calm, but then again, we were a pragmatic family. Faced with a problem, we got right to solutions, and tried to return to normal as quickly as possible.

“Mom, I think it’s too late for me to get a plane into Tampa tonight. Did you talk to Barbara?”

Barbara, four years older and my only sibling, lived in Arlington, Virginia, just a few miles from where we grew up.

“I’m going to call her now,” Mom said.

“Do you want me to call her?” I asked.

“No, I’ll do it.”

“Tell her to call me so we can coordinate our flights. We’ll hook up at the Tampa airport tomorrow and rent a car.” Now I was in problem-solving mode.

“I can pick you up.”

“No, Mom, let us get a car. I’ll call you in the morning. If you need anything, though, call me tonight. Call me anytime. I’ll keep the phone by the bed. I love you, Mom.”

In our small family circus, Daddy had played the role of benevolent owner. He had supported us all through his hard work and smart investment decisions. He’d kept the tent mended, and entertained us with bad jokes and painfully clever puns. Mom was the ringmaster, making sure the show ran smoothly. She encouraged my desire to perform, and tried to coax Barbara from her chosen seat behind the curtain. Barbara and I were expected to be responsible and proceed with caution, but Mom and Daddy always offered a safety net if we got into trouble.

In recent weeks, Daddy had been the one in trouble.

“He keeps saying he just doesn’t feel like himself,” Mom had told me a few days earlier.

They’d seen the doctor that morning, and Daddy was scheduled for tests the following Monday to see if his carotid artery, the one that carries oxygenated blood to the brain, was partially blocked.

I’d been worried for a while. A month before Daddy died, I’d called to tell my parents the good news that Klein and I were engaged. I was forty-two and this was my second marriage, the first having ended ten years before in an unpleasant divorce. Mom and Daddy had met Klein. They liked him, and could see that we were happy together.

Daddy answered the call, and I told him how Klein had proposed on Valentine’s Day on the beach. He said, “That’s good, Mel, real good. Mom’s not here, but I’ll tell her as soon as she comes back.” His voice was flat, and it scared me. The man I grew up with would have whooped and said something like, “Geez, Mel, that’s the nuts! He is one lucky guy.” I hung up the phone and cried. I knew Daddy had suffered a few small strokes, but until that conversation, I hadn’t realized how much they were robbing him of his ability to feel or express his usual joie de vivre.

The day after Daddy’s death, Barbara and I met at the Avis counter at the Tampa airport. Her eyes were red, and we both teared up when we hugged. On the forty-five-minute drive to Gulf Harbors, we caught up on our lives and work, laughed about Daddy’s favorite landmark—the giant white, red, and green concrete cowboy boots at the entrance to Boot Ranch, home of Al Boyd’s award-winning Brahman cattle—and speculated about what had killed our father. Had a stroke brought on the choking, or the other way around? Did it matter?

At the condo, we dragged our suitcases into the narrow front hallway and called to Mom. Everything seemed the same as always—the immaculate lettuce-green carpet, the dim light filtering in from the sunroom, the small arrangement of blue and white silk flowers on the dining table, the quiet hum of the air conditioning, and the faintly sweet, leathery smell of Daddy’s pipe tobacco. Was he really gone?

Mom came out of the bedroom. Even she looked unchanged—sturdy, well-groomed, and, at five-foot-one and one hundred-forty pounds, nicely cushioned. Her thin white hair was teased into a poufy cloud above light blue eyes, a large, straight nose, and bright red lips. She wore her uniform of indestructible polyester knit stretch slacks, print blouse, and suede-strapped wedge sandals. Barbara and I moved in for a group hug, creating a five-foot pillar of Pratt women.

“I’m okay, really, I’m okay,” Mom said. “Put your suitcases in the guest room, and let’s have some lunch.”

We each made a sandwich from the cold cuts Mom had laid out, and took them to the table in the sunroom.

&

nbsp; “What happens next?” I asked Mom.

As usual, she was ready to face the situation head-on and take charge. Mom was smart—Swarthmore, class of 1937 smart—and supremely capable. Before Barbara was born, Mom had worked as an editor at the John C. Winston Company, then as assistant to the medical director at Capital Airlines. When Barbara and I were growing up, Mom had run our home like a skilled executive from her turquoise Formica-topped desk in the kitchen. She’d kept track of our school activities, doctor’s appointments, ballet and piano lessons, and Daddy’s work shifts as a maintenance dispatcher (also at Capital Airlines). Everything was marked on the Girl Scout calendar that sat below the yellow wall phone with the long, coiled cord. Next to the calendar was the flip-up A-to-Z aluminum telephone directory, with numbers for doctors, schools, the housekeeper, and all our friends, available at the touch of a button.

Mom still had that ancient directory, with old entries crossed out and newer ones in various colors of ink. She’d been using it all morning.

“We’ll have to go to the funeral home tomorrow and finalize everything. You know he’ll be cremated. I called Keith at Merrill Lynch, and the lawyer, and the accountant. We can’t do anything else until I get the death certificate,” Mom said.

Barbara and I knew all about our parents’ finances. On more than one of my previous visits, Daddy had sat me down at the breakfast table and pulled out the three-ring binder of Merrill Lynch statements. He’d explained over and over how all their assets were in a living trust that would make it easy to transfer everything to Mom, or to him if she died first, and to me and Barb, once they were both gone. He had made sure Barbara and I could locate the keys to the fireproof safe that sat on the floor of the storage closet. In it were the trust documents, wills, living wills, and paperwork for their prepaid cremation.

Holding the Net

Holding the Net