- Home

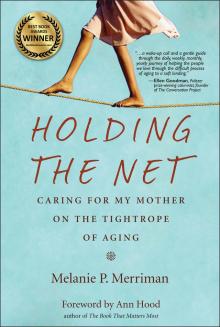

- Melanie P. Merriman

Holding the Net Page 2

Holding the Net Read online

Page 2

Next to the safe was the file cabinet with medical records, insurance documents, utility bills, and condo papers. Daddy and Mom each had a file labeled In Case of Death—as if it were optional.

After lunch, I went into the closet, pulled out Daddy’s folder, and read through the contents: a copy of the prose poem Desiderata, by Max Ehrmann; a list, written on a piece of lined yellow legal paper, of some of his favorite music, including The Planets by Gustav Holst and Carl Orff’s cantata, Carmina Burana; a letter from someone he had worked with at Capital Airlines, praising his sound judgment and sense of fairness; and an autobiography in Daddy’s handwriting from his junior year of high school. He’d received an A+. I had never seen them before, but each item reflected how deeply he had cared about people, and the way he had wanted to be remembered.

I have to write a eulogy, I thought. We have to have a service. Daddy’s death had been too sudden. I wanted to keep him alive a little longer. I wanted to honor his memory, and give others the chance to honor him, as well.

I told Barbara my idea.

“Look, I’d really like to do something, too, but you know Mom won’t want to,” she said.

Mom and Daddy had said many times that they did not want any kind of funeral service. I’ll never know why they felt so strongly. Maybe they thought funerals were sad, and even if they couldn’t protect us from death, they would try to protect us from sadness. After they had mentioned it two or three times, I probed a little to see what might be acceptable.

“Can’t we at least invite people over for brunch?” I’d asked them. “Your friends will want to pay their respects.”

“We just don’t want any fuss,” Mom said.

“There’s no need to make a big deal,” Daddy added.

At five o’ clock, Barbara, Mom, and I headed to the sunroom with our drinks. Mom sat in her chair, and Barbara and I sat in the side chairs that rocked and swiveled. No one sat in Daddy’s chair.

I leaned over to the TV table holding the snacks, dipping some hummus onto a cracker.

“Mom, I want to have a service for Daddy.”

“Mel, you know he didn’t want anything like that,” Mom replied.

“I know he said he didn’t, but then he carefully prepared all this.” I picked up the blue folder.

“We both have folders,” Mom said. “It’s stuff to use in an obituary.” I rocked my chair a couple of times. “Mom, I just think there is a lot more to say than what we can put into an obituary. I want to tell people what he meant to me.”

“I do, too,” said Barbara, her voice catching.

Mom sipped her martini and reached for a tissue.

“I just don’t know,” she said, wiping her nose. “We always said, no services for us.”

“Well, the service isn’t for him, it’s about him,” I told her. “It’s for me and you and Barbara, and for everyone else who wants to say goodbye. It doesn’t have to be anything elaborate. Mom, I need to do this.”

“Where would we have it? I can’t do anything here.” Mom looked down, folding her hands onto her lap. “And when would we have it? You girls need to get home, back to your lives and your jobs.”

Barbara rattled the ice cubes in her bourbon. “Mom, we can stay for a few days. I can’t even think about work right now, and Phil will be fine without me.”

Barbara’s first marriage, like mine, had ended in divorce. She had married her second husband, Phil, just three months before Daddy died. She didn’t have children, but Phil had a son who spent some weekdays and weekends with them. Barbara worked as a paralegal, mostly on environmental cases and mass torts—like seeking compensation for families of holocaust survivors whose assets had been taken during the war—for a large firm in Washington, D.C.

Klein and I had no immediate plans for a wedding, and no children. My first career had been as a research scientist on the faculty at the University of Miami School of Medicine. In 1992, two years before Daddy died, I’d finished an MBA in Health Care Administration, and changed careers. Now I worked for a national provider of hospice services, home-based care for people near the end of life. They had a generous policy about bereavement leave.

“I agree,” I said. “This is the only place I want to be right now.”

“Well, I’m glad you’re here,” Mom said, “but you know Daddy wouldn’t want any commotion.”

“I know, but we don’t have to pretend that nothing has happened,” Barbara said. She picked up her glass and headed for the kitchen. “I need a refill.”

“Look, Barbara and I will take care of all the arrangements,” I said to Mom. “What about having it in one of the condo clubhouses?”

“No, you can’t use the clubhouse for anything personal,” Mom said.

“Maybe the funeral home would provide a room.”

“Maybe.” Mom spread some cheese on a cracker. I reached for the hummus and forced myself to keep quiet.

“Okay,” said Mom, “but it won’t be a funeral. It will be a memorial service.”

“Good,” I said. “A memorial service is just right. We can put the information about it into his obituary.”

The next day at the funeral home, Mom signed all the papers for the cremation, and we asked if they would rent us a room where we could conduct a memorial service. The only room available was a chapel that held two hundred, far bigger than we needed. Mom thought it was expensive. As she took out her checkbook, I told her I would pay. She wouldn’t let me, but said Barbara and I could buy some flowers to decorate the room.

Two days later, we were back at the funeral home, setting up for the service. The newspaper had made a mistake, and Daddy’s obituary hadn’t been printed yet, so we only expected a small group of his and Mom’s closest friends.

Barbara placed the flowers at the front of the room, and I put a copy of The Planets on the CD player at low volume. Daddy had been a hi-fi buff, and I imagined him cringing at the pathetic sound system. Every night, when we were kids, he would go to the basement after dinner and listen to classical records or reel-to-reel tape recordings through two speakers the size of small refrigerators. After the move to the condo, he had to substitute smaller speakers, but they were still powerful.

“Sometimes, when your mom is out at the grocery store,” he had once confessed to me, “I crank up the volume until the sheer beauty of the music shoves me up against the back wall, gasping for air.”

At the service, Mom sat in the front row. She kept turning around to watch as more and more people arrived. Somehow, even without the obituary, word had spread about the memorial service. I thought about the ending of It’s a Wonderful Life, and hoped that Daddy, like the Jimmy Stewart character in the movie, could see how much he had mattered.

My parents, Eleanor and Dave Pratt to their friends, were part of the fabric of their Gulf Harbors condominium community. They had moved in twenty years earlier, during one of the first phases of construction. Daddy considered a warm Florida retirement to be the reward for working hard and taking good care of his family. He’d had to drag Mom out of our Northern Virginia home, but within a year or so, she had settled in. She served as president of the 537-unit condo association for two years, then became editor of The Comet, the community newsletter. Daddy had a rack in a kitchen cupboard that held about ten sets of extra keys, each neatly labeled with the name of a couple who had asked him to check on their homes when they were out of town. Once, one of the clubhouses burned down, and Daddy had designed and overseen construction of the new one.

At the service, I read my eulogy, quoting Erhmann’s Desiderata (“As far as possible, without surrender, be on good terms with all persons”) and extolling Daddy’s sense of personal responsibility and willingness to help anyone who needed it. “Whenever I see that bumper sticker about random acts of kindness and senseless acts of beauty,” I said, “I always think of my dad.”

Barbara shared what she called her “mental videos” of Daddy: when he taught her to drive while explaining th

e workings of the internal combustion engine; when he described why one should always tell the truth (because it’s too hard to remember your lies); and when he was just enjoying life…the way he would lean back after a good meal with family and friends, put his hands on the table, roll his eyes to the heavens, and shout, “Man! I just love these kinds of carryings-on.”

Though she had sworn she would not, Mom said a few words, then invited others to share memories. I don’t think anyone said anything sad, other than the obvious—that he would be missed.

After the service, when everyone had left and we’d come back to the condo, Mom gave her assessment. “Okay,” she said. “You can do a service like that for me.”

I laughed and enjoyed a moment of self-satisfaction. “We’ll see,” I said. “It will be a long time before it’s your turn.”

And then it hit me. Mom was only seventy-eight, and had years ahead of her without Daddy.

I hadn’t planned for this. I had spun myself a myth that my parents would go about their independent, happy lives—then, one day, they would die simultaneously, preferably in their sleep.

Until Daddy’s recent strokes, they had been pretty much living my myth. They’d been married for fifty-three years, were still in love, and fulfilled comfortable, well-established roles. Mom did the grocery shopping, cooked the meals, and managed their social life. Daddy took care of the car, did minor maintenance projects in their condo, and managed the finances. They both cleaned the house and did laundry. Mom also kept busy with bridge and women’s groups, her “job” as editor of The Comet, and arranging trips to dinner and the theater for condo residents. Daddy preferred to stay home and read or listen to music. He liked his routines, but he encouraged Mom to go and do whatever she enjoyed. And when she felt overwhelmed, he offered a warm hug and a calm voice to let her know it would all work out fine.

There had been only two hospitalizations, neither of crisis proportions. When she was seventy, Mom had been diagnosed with breast cancer. It was a tiny tumor, but at the time, standard treatment was a full mastectomy. There were no complications, and she didn’t receive radiation or chemotherapy. The summer before he died, Daddy had back surgery, a routine laminectomy, to relieve pain in his leg.

In my hospice work, I was immersed in end-of-life scenarios that featured advanced illness and the need for intensive symptom management. I was becoming an expert in quality of life for hospice patients—but none of that would help me now. Daddy hadn’t needed hospice care; he died almost before anyone realized he might be near the end of life. And Mom was very much alive and healthy.

My myth had been shattered.

The sunroom at Mom and Daddy’s condo in New Port Richey, Florida. I took this picture in 2007.

Chapter 2

THE NIGHT OF THE MEMORIAL, Barbara and I, each with an opened book, tucked into the well-worn flowered sheets on the twin beds in Mom’s guest room. After a few minutes, I realized I was reading the same paragraph over and over.

“How do you think Mom is doing?” I asked.

“She seems fine.” Barbara kept reading.

“I know. Is that weird? Do you think she’s in shock? Maybe I’ll suggest she come home with me for a few days.”

“She won’t go. She doesn’t want to…be a burden.” We said those last three words together, like a chorus, and laughed.

This was Mom’s frequent refrain, and though her motives were noble, it often came up in ways that seemed self-serving—like Daddy’s 70th birthday dinner at Rossi’s Italian Restaurant. We were playing What if you won the lottery? and Barbara had said she would quit her job and buy a big house with a greenhouse and lots of gardens. Her husband said he’d buy a Maserati. Daddy said “Me, too.” Then it was Mom’s turn.

“I just don’t ever want to be a burden on my girls,” she said.

We all blew her raspberries.

“No fair!” I said.

“No fun,” said Barbara.

“Well, that’s my answer,” Mom had said as she wiped at her eyes with her napkin.

Game over.

I half sat up and leaned on my elbow to face Barbara in the other bed.

“But seriously,” I said. “What happens now?”

After a moment, Barbara put down her book and looked straight ahead.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I just don’t know.”

If nothing else, I figured we would need to be there for Mom in ways that had simply been unnecessary before, and I knew it would be more me than Barbara. Of course, it was easier for me to visit from Miami than for Barbara to come down from Virginia—but the main reason it would be me was that Mom and I liked each other. Mom always said that she and I were sympatico. Barb and Mom, on the other hand, maintained a polite and superficial relationship. They rarely saw each other, and never spent more than a long weekend together. Mom and Barb were family. Mom and I were friends.

Mom and I had always been close. When I was young, I needed her, and she liked to be needed. I was eager to start school, so Mom put me in kindergarten at only four years old. Though intellectually more than ready, I was emotionally crippled by separation anxiety. Mom volunteered as a teacher’s assistant so she could be in the classroom for the first few hours of each day until I got my sea legs. I didn’t understand exactly what was going on, but even then, I knew I would not have made it without her.

Also, Mom and I were both extroverts who liked to go and see and do. Mom had to push Barbara to join the Brownies, while I begged to be in their talent show two years before I was old enough to join the troop. Like Mom, who had been in plays in high school, I was eager to take ballet and be in the recitals, in spite of terrible stage fright. Mom encouraged all my exploits.

Even through my senior year in high school, I’d come home from school and tell Mom all about my day. She was interested. She offered advice. We didn’t always agree, but we always wanted to know what the other thought.

Barbara was more of an introvert, and she liked her privacy. When she came home from school, she headed straight for her room and shut the door. Mom was just as eager to hear about Barbara’s day, and just as eager to share her opinions about what Barbara should do—but Barbara didn’t seem to care what Mom thought, or what Mom wanted her to do. Like most teenagers, she cared more about what her friends thought.

Mom had strong opinions, which she stated as if they were fact. Instead of saying “I like your hair better short,” she’d say, “Your hair looks better short.”

I ignored it, but Barbara bristled.

“I like it long,” Barbara would say.

Mom tried other ways to connect, pressing Barb for information.

“How are things at school? Did you decide to write for the newspaper?” Mom might ask when Barbara came into the kitchen for a snack.

“School’s okay. I haven’t decided about the paper.” Barbara would stare into the open refrigerator. Then she’d grab an apple, take a bite, and head back down the hall to her room.

I loved Barbara. I wanted to be her. I couldn’t wait to fit into her hand-me-downs—but I didn’t feel like I mattered much to her. And really, why would she want to be my friend? She was four years older, and I was a fragile, nerdy, goody-two-shoes. Knowing that my frequent attacks of nerves disrupted the family, I tried to compensate by bringing home excellent grades, staying out of trouble, and doing whatever was asked of me. For the most part, Barbara and I were just two people growing up in the same house.

As we got older, graduated college, and married our first husbands—and as I became more independent, less fragile emotionally, and less attached to Mom—Barbara and I started building a real friendship. Then we discovered we had a lot more in common than we’d ever thought. The anxiety I’d suffered as a little girl continued into adulthood in the form of panic attacks. I’d have good months and bad months, even good years and bad years. I knew something was wrong with me. I didn’t want anyone else to know. I lived a full life, but cautiously.

&n

bsp; When I was twenty-four and Barbara was twenty-eight, she had her first panic attack, and then another and another, until the unpredictability and severity of the symptoms developed into agoraphobia. She was afraid to go anywhere or do anything. She thought she was going crazy. Finally, knowing I would understand because of my own struggles, she called me.

“You are not crazy,” I told her. “I know it feels that way, but I promise, you can and will get better. I’ll send you the name of the psychiatrist I used to see. He’s good. He’ll help you.”

“Could you call him for me?” She was crying so hard I could barely understand her.

“Yes,” I said, “I’ll get the first available appointment. Will Skip take you?” Skip was Barbara’s first husband.

“I don’t want to ask him. He’s been completely supportive, but I’m afraid he’ll get tired of my being so dependent on him.”

“Do you want me to come down?” I asked.

I was in the last stages of my PhD program at Brandeis University in Waltham, MA, deep into editing my thesis.

“Oh, Melly!” I heard fresh tears. “How can you do that? I wish you could.”

“I can, and I will,” I said.

“I’ll be there tomorrow.”

I threw my thesis and some clothes into a suitcase and flew to Virginia. I found Barbara curled up on the couch in her living room, wrapped in a blanket. As we hugged, she sobbed into my shoulder. Years later, she would tell me that she had been afraid and anxious as a kid, just as I was; that she’d been furious with Mom for making her do things she was afraid of, like joining clubs and performing. Her bedroom was her escape, the safe place where she could retreat from the real world into a book. But this full-on, uncontrollable panic was new to her.

“I promise this will get better,” I told her. “I have been there, and I know there are ways out.”

“I hate this. I hate myself. Why can’t I get up and fight?” she asked.

“It’s biochemistry,” I explained, “not a moral failing. You’re all out of whack. I don’t know why, but I know it’s not your fault. We have an appointment with the doctor tomorrow morning. That’s the first step.”

Holding the Net

Holding the Net